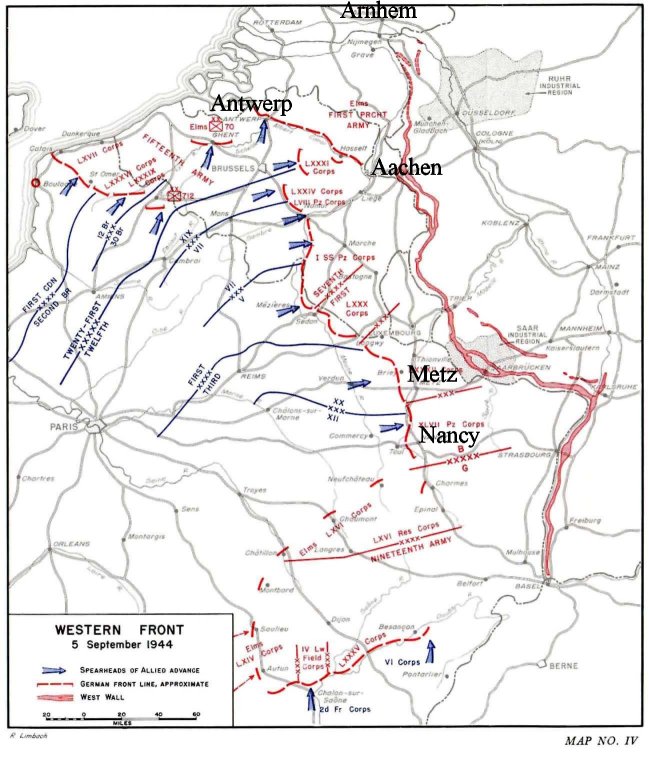

The German army was retreating toward Germany as quickly as possible, including units from southern France pursued by the US 7th Army which had landed on France's Mediterranean coast. Although the Germans from the south of France were not cut off, the situation for Germany was bleak. They had recently lost 900,000 men against the Soviets, 300,000 in Normandy, and 200,000 men were being surrounded by the Allies in port cities. Seven hundred thousand did remain on the Western Front. The Germans were also sending new units forward, including a division from Italy to Lorraine. The bulk of these new units were headed to the Moselle to face Patton, so from September 1st to September 5th, the German force in Lorraine went from three and a half to eight divisions.

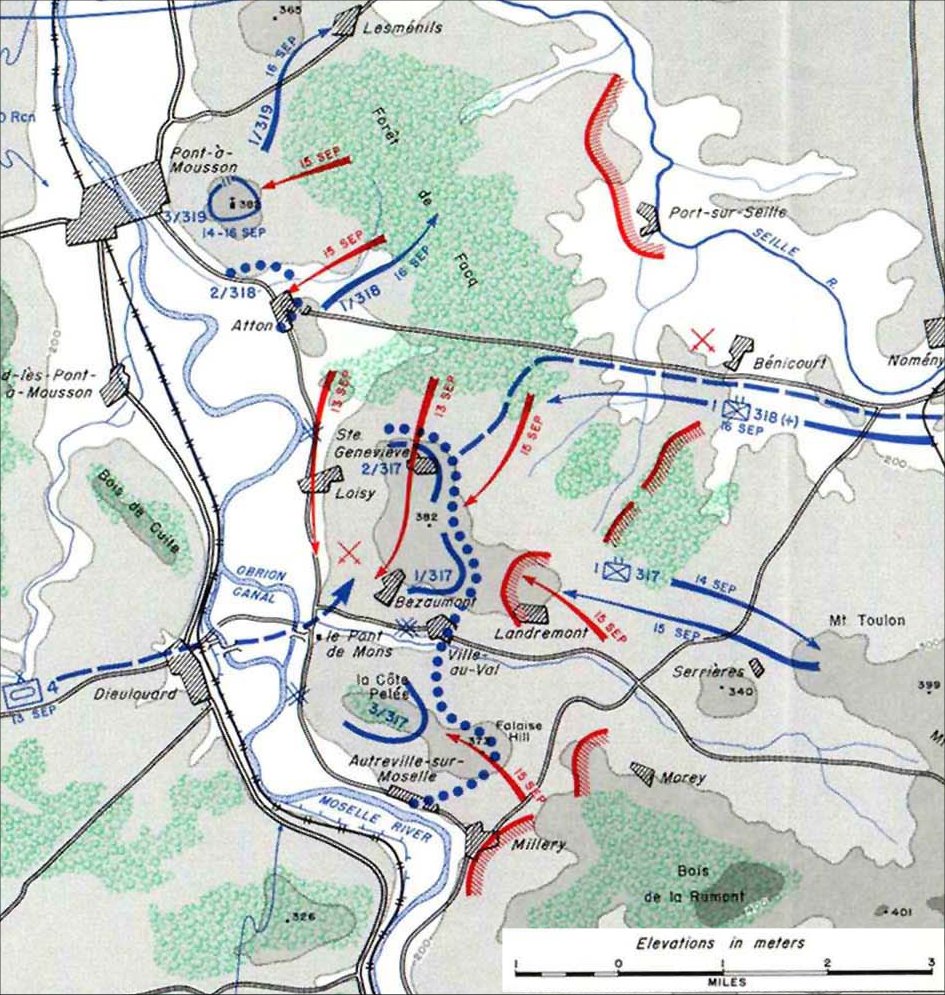

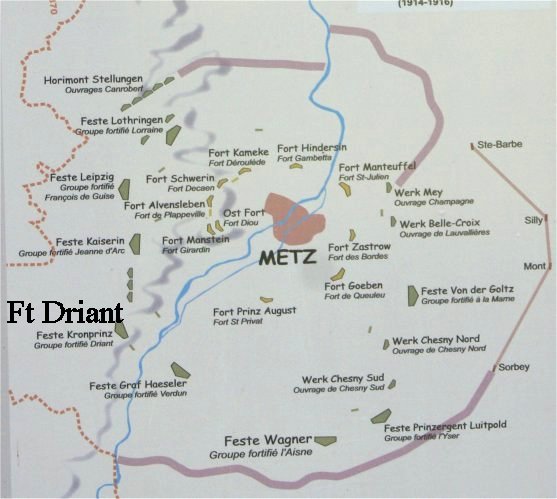

With expedients like the Red Ball Express the supply situation improved somewhat, and Patton still believed that he could regain his previous momentum. It would not be easy. Once composed of three corps, the detachment of a corps to Brittany which became the 9th Army had weakened Patton's eastward drive down to two corps, each with three divisions. Since the 3rd Army was ahead of the other Allied armies, one division from each of Patton's corps was assigned to flank protection. This left just four divisions to continue the advance over the Moselle - this over a front of 75 miles. The Germans had eight divisions, well below strength, but they were able to achieve manpower parity along the Moselle. The Allies were greatly superior in equipment and despite supply problems, mobility too. Patton ignored intelligence showing that the Germans were consolidating and strengthening along the Moselle, and he thought little of the river in front of him and was instead focused on breaching the West Wall and crossing the Rhine.