Civil War Tactics in Perspective

Which Civil War historians also research and write

about the Napoleonic era, the eighteenth century, or other wars of the

19th century? There are very few - but the rare ones who

do give us

the greatest insight into Civil War combat. How can you

understand Civil War tactics without perspective, without studying what

Civil War generals studied, without comparing Civil War weapons to

those that came before and after? You cannot. How can you

understand Civil War tactics by looking solely at the infantry?

Many Civil War historians attempt just that, getting bogged down in the

minutiae of battles instead of gaining perspective by researching and

understanding other

eras. Because of this lack of perspective, many historians don't

fully understand why

Civil War combat was indecisive. And because of their lack of

background, when historians specializing in the Civil War have seen

Civil War generals write of "Napoleonic" tactics, firstly - they may

not have understood the sort of tactics used by Napoleon - something more

than

just men fighting shoulder to shoulder - and secondly, it didn't occur to

them that "Napoleonic" might refer to another Napoleon, Napoleon III.

Mid nineteenth century French tactics were an evolution of earlier

tactics and included a faster

'gymnastic' pace of attack to reach enemy lines faster, hopefully

negating the advantages of the new rifled musket. (The Bloody

Crucible of Courage, Brent Nosworthy)

As discussed elsewhere, the rifled musket, although a technological

advance, was not the revolutionary weapon that it has been made out to

be. Artillery, on the other hand, was much improved from fifty years

before.

What were Napoleonic tactics, and how

do they differ from Civil War tactics?

|

If you understand how Napoleon fought, you will see that Civil

War tactics were different in a number of important ways.

These differences perhaps explain much of why Civil War

combat tended to be indecisive.

In the gunpowder age, battle was often indecisive.

Napoleonic combat, the ultimate development of linear tactics, is

the exception. Napoleonic tactics were the evolution of

linear tactics born with the socket bayonet. One hundred

years before Napoleon, an infantry battalion was an unwieldy and

vulnerable combination of musketeers and pikemen, with the pikemen

protecting the musketeers from enemy pikemen and cavalry.

With the socket bayonet, musketeers shed themselves of pikemen -

now they could protect themselves from shock attack and still fire

their muskets. Over decades, musketeers stretched themselves

thinner, first into six ranks, then four, then three, and finally

just two. It was still an awkward system in some ways, with

difficulty deploying an army from the march into line of

battle. In Marlborough's day, in the early 1700s, it took

most of the day to prepare for battle, and it was impossible to

surprise an enemy on the march. When battle began, the whole

of the infantry would typically attack together simultaneously in

two lines. The logical place for cavalry was on the

flanks. In battle, the cavalry would defeat the opposing

enemy horsemen then attack the rear of the enemy infantry just

like in the 1600s - but also, at least in theory, much like the

American Civil War.

Frederick the Great perfected this system, marching and

deploying on the enemy's flank for a devastating attack.

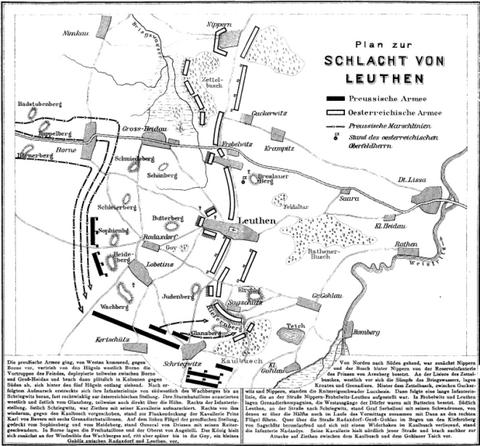

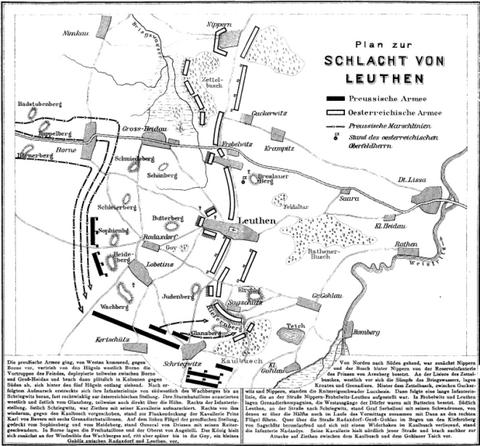

Frederick's attack at Leuthen, and his later attempts to do the

same, looks similar to Jackson's attack on the XI Corps at

Chancellorsville and Early's attack at Cedar Creek.

Indeed, in many ways the Civil War looks more like the Seven Years

War than it does the Napoleonic Wars.

By Napoleon's time, battle was more flexible - thanks to

advances in infantry tactics.

With the use of thinner battle lines - two or three ranks - a

quicker, simplified system was developed to deploy from marching

column into line of battle. Battle was becoming more

practical, no longer a rare and consensual event.

Let's take a look at change in the 18th century and the

development of Napoleonic tactics, one feature at a time.

|

|

Artillery

There was plenty of room to improve upon mid-18th century tactics, and

the defeated and humiliated French army lead the way with reform.

The Austrians had already made great strides in reducing the weight of

their cannon, with their new pieces weighing only half as much as their

predecessors. The French adopted these concepts with the

Gribeauval system. Frederick had already complaining in the Seven

Years' War that the new Austrian artillery was killing off his highly

trained infantry, who were renown for their discipline and quick rate of

fire. The new lighter field artillery had the potential to

revolutionize warfare. There was no choice for a monarch but to

enter into an artillery arms race - or else have his army

slaughtered. Masses of the new mobile guns, grand batteries, could

be brought to bear against the enemy, blowing holes in his line and

demoralizing his men.

Skirmishers

Frederick was also whining that Austrian light infantrymen sent ahead

of their main line were picking off officers and men while taking cover

behind trees and terrain features. With an army made in many cases

of forcibly recruited men held in bondage only by the threat of severe

punishment, Frederick couldn't trust his men to go forward and

skirmish. With the prospect of freedom, they might run away and

never be seen again. Frederick resisted this change, at least for

a while, before embracing it. Other armies developed highly

trained and motivated special units of light infantry too.

Although skirmishers of the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic

times are often stereotyped as ill-trained levies good for nothing more

than swarming in dense masses in front of the enemy line, modern

historians dispute this. Whenever possible, skirmishers of the era

were highly motivated, well trained, and good shots. Their calm,

slow, well-aimed fire, combined with artillery, gradually wore down the

enemy and un-nerved the survivors before the main attack.

Columns

A misunderstanding of early English-speaking historians has distorted

our understanding of a major aspect of Napoleonic warfare - the use of

columns. Focusing on the Peninsula War and relying almost

exclusively on British sources, some historians came to the misguided

conclusion that the French primarily used battalions of infantry for

shock action in columns of attack. As early as the mid 1700s the

French were keeping their second line in column formation to allow for a

flexible response to problems or opportunities on the first line.

During the 1777 Battle of Brandywine, the British army, generally

thought of as conservative, advanced on the rebels in maneuver columns

then deployed into an open-order line. By Napoleonic times French

infantry, preceded by skirmishers, advanced toward the enemy in

battalion-sized columns for more flexibility and maneuverability on the

battlefield, allowing them to adjust to enemy deployments, better seize

opportunities, or attempt to flank the enemy line. Before

contact with the enemy, however, the columns would deploy

into line for the firefight. A bayonet charge in column formation

was only done after gaining firepower superiority when the enemy troops

looked shaky and on the verge of breaking. Against most armies,

this method worked very well. The infantry's increased flexibility

helped in other ways. The infantry columns also allowed much

closer cooperation with the artillery, which was better able to mass

against a portion of the enemy line or even move forward with the

infantry. Closer co-operation with the cavalry was also

possible. Unlike in the 18th century, cavalry could advance right

along with the infantry, and the infantry was not restricted to an

attack by the whole army.

Cavalry

While 18th century cavalry was placed exclusively on the flanks, the

new infantry columns allowed the mounted arm to advance in columns

directly in support of the infantry, and even change places with them to

lead the attack. To protect themselves. enemy infantry would form

squares, but in so doing they deprived themselves of much of their

firepower and their ability to maneuver. If artillery could be

brought forward, the enemy squares would be blasted out of

existence. Either way, a massive hole was formed in the enemy

line, and decisive victory was assured.

In terms of grand tactics, Napoleon would typically threaten the enemy's

flank, forcing him to commit his reserve. He always kept a large

reserve available, a vitally important part of his system, to either

exploit success or stave off defeat. Most often, with the enemy

reserve committed, Napoleon would send his own reserve into the weak point

in the enemy line and secure a decisive victory.

Co-operation among all three combat arms was key to Napoleon's

system, and the reserve decided the battle.

Does this sound like Civil War tactics to you? No, far from

it! Civil War armies kept few reserves, and Civil War combat

featured little in the way of combined arms cooperation. Unlike

the Napoleonic Wars, and more like the 18th century, reserves

were a rarity in the Civil War, and a commander had few options once a

battle "developed" to maturity. Civil War tactics were NOT

Napoleonic, at least not in the sense of Napoleon I.

|

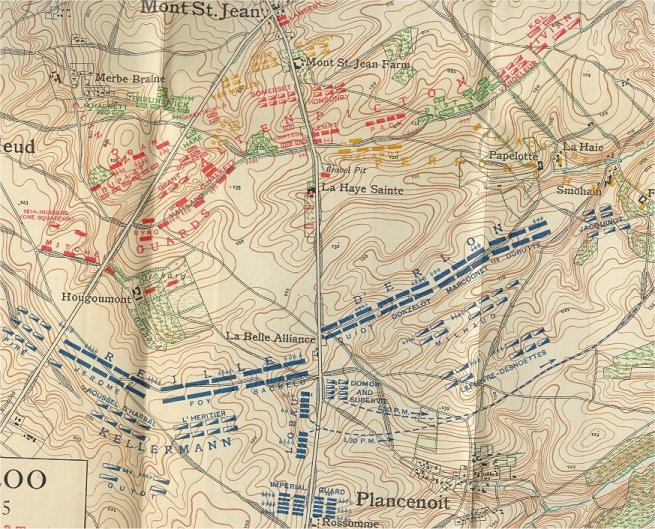

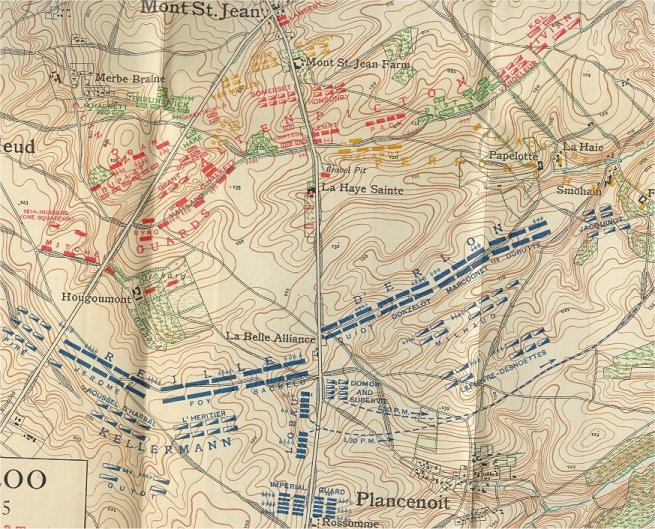

| Map of the Battle of Waterloo, 1815

Note that Napoleon's army (in blue) has cavalry not only on the

flanks but also behind the infantry. The same is true for

Wellington's army. Also note that Napoleon has a large

reserve composed of Lobau's corps and the Imperial Guard.

This deployment is very unlike that of a Civil War army.

|

|

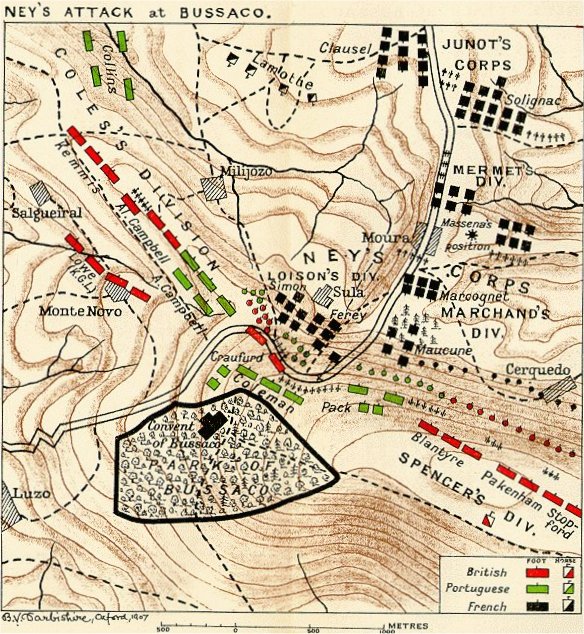

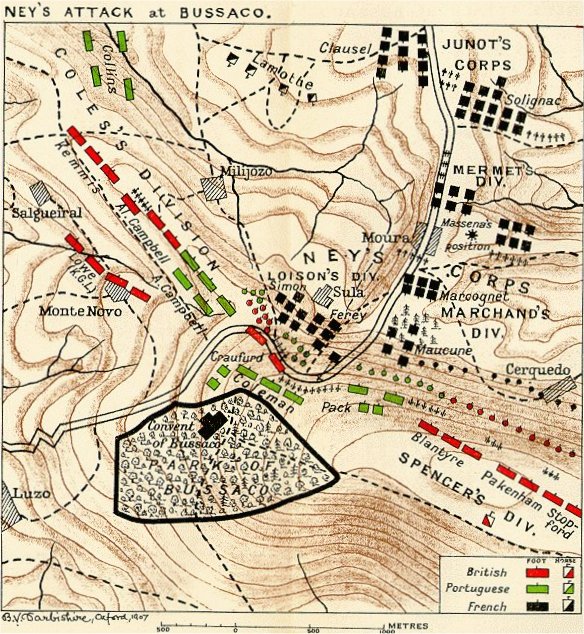

| Map of Bussaco, 1810 - Napoleonic Tactics Gone

Bad

In the rough terrain of the Iberian peninsula, French

artillery was less effective, and cavalry couldn't cooperate

very easily with infantry. Here at Bussaco, large numbers of

British skirmishers hid the infantry line and allowed a surprise

volley followed by a decisive bayonet charge on the un-deployed

French columns.

|

French tactics in Spain and Portugal didn't work out so well, and their

old school British opponents may have never understood their intent.

Rough terrain complicated the system considerably. It was difficult

to mass artillery batteries, and it was difficult for cavalry to support

the infantry. Wellington sometimes sent as much as one third of his

men forward as skirmishers, and the French could never gain superiority

over them. Since Wellington kept his infantry hidden behind the

reverse slope, the French maneuver columns blundered upon the British line

and were surprised. Struggling to deploy into line and disorganized

and shocked by the surprise encounter, the French received one or two

close range volleys from their British opponents who then let out a cheer

and charged. The British system worked consistently, except at

Albeura - and at Waterloo, where the open terrain suited Napoleon's

methods. Terrain explains much of the British success against the

French. In part, terrain also explains why combined arms tactics

were so rare during the Civil War, but we'll discuss that later.

Perhaps because of the British success, and because of the bloody nature

of Napoleon's later battles, post-Napoleonic military theorists became

somewhat reactionary and supported tactics which looked backward to the

18th century. Napoleon's later battles became less decisive, partly

because his enemies adopted his methods, and partly because the greater

firepower from more artillery made attacks less likely to succeed.

Civil War Tactics Look Like a Poor

Man's 18th Century

The first American army, the Continental Army, was based on its British

opponent during the Revolution; even then, the British were known for a

brief musketry exchange followed by a charge. Civil War tactics

don't resemble this, or British Peninsula tactics, or Napoleonic

tactics. But Civil War tactics do resemble the 18th century in that

infantry was typically formed in two lines flanked by cavalry. Civil

War battles sometimes even featured a Frederican style oblique order

attack.

Although Gettysburg featured a Napoleonic concentration of artillery,

genuine Napoleonic tactics for example, would have involved cavalry

supporting Pickett's Charge - and Union cavalry charging in pursuit of the

defeated Confederates- in short, it would have been combat with the

potential for decisiveness. The technology of rifled muskets didn't

make this sort of thing impossible. Koniggratz in 1866 shows this as

do some later Civil War battles like 3rd Winchester. Because

combined arms attacks weren't regularly attempted, battle was predictably

indecisive.

Unlike Napoleonic and eighteenth century battle, all too often, Civil War

combat degraded into a confused infantry firefight with officers gradually

losing control, with any hope for maneuver lost. After the onset of

confusion, shock action with the bayonet was not practical. Due to

lack of training and discipline - an inevitability to some degree with a

volunteer army of a democratic government - it was always difficult to get

men to close with the enemy. Once an infantry advance stopped in

order to fire, it could rarely be made to continue forward. GFR

Henderson wrote on page 215,

"Occasionally, when protected by

unusually strong defenses, the leaders were able to induce their men to

reserve their fire to close range, but, as a general rule, whether

defending or attacking, the men used their rifles at will. The

officers were never sufficiently masters of their soldiers to prevent

them, when bullets were whistling past, from immediately answering the

enemy's fire. In the best Confederate regiment, in the midst of a

conflict, the ardent and burning inclination of the soldiers was obeyed

rather than the commands of the officers."

Prussian observer Justus Scheibert believed that a deficiency in lower

level officers, who showed "ignorance of military things", explained

why the brigade became the tactical unit of the war, "hence stiffness in

the lines and clumsiness in management and direction of troops".

Poor performance on the battlefield was the result, and "the loss of an

upper-level commander would cripple (the) advance". He described an

attacking infantry division as "like ghosts of days and ways of Frederick

the Great.", in essence a poor man's version of mid 18th century

methods. (Scheibert 49) He described a typical attack;

"The nearer to the enemy, the more faulty the lines and the more

ragged the first (line) until it crumbled and mixed with the

skirmishers. Forward went this muddle leading the wavy rest.

Finally the mass obtruded upon the point of attack. In a

sustained, stubborn clash, even the third (line) would join the

melee. Meanwhile the usually weak reserve tried to be useful on

the flanks, or stiffened places that faltered, or plugged holes.

In sum it had been a division neatly drawn up. Now its units,

anything but neat, vaguely coherent, resembled a swarm of skirmishers."

(Scheibert 41)

In contrast, Scheibert writes:

"Prussian tactics freed (officers) to use their own minds...

Liberated battalion and even company commanders could be the heads of

tactical units, their own, and make them fight as right-thinking

officers saw fit and as well-trained troops best could. The

flexible line at the forward edge resembles a chain, then with

detachable links under independent guidance. At crisis they can

dismember into smaller and even the smallest units without

dysfunction... Our Prussian tactics thus gave our line officers

energy, elasticity, and speed - to the entire army's benefit...

Furthermore, diligent peacetime training provided our troops an

abundance of formations, something to fit any circumstance... Lee,

the first American to acknowledge this superiority, replied in the thick

of Chancellorsville when I spoke with amazement at the bravery of

Jackson's corps: 'Just give me Prussian formations and Prussian

discipline along with it - you'd see things turn out differently here!"

(Scheibert 49)

An extreme example of how potentially decisive combat degraded into chaos

is Brawner Farm. Jackson had the opportunity to attack and crush an

isolated and much smaller Union division with his corps, but the attack

stalled, and an indecisive firefight resulted, and because of Jackson's

peculiarities, his subordinates feared to take the initiative and stood

idly by while the opportunity to destroy a Union division was lost.

The human element is important in combat. Men are not machines,

and American volunteers were not European professionals. The

Comte de Paris wrote in his "Campagne du Potomac" on pages 144-4:

"The will of the individual, capricious

as popular majorities, plays far too large a part. The leader is

obliged to turn round to see if he is being followed; he has not the

assurance that his subordinates are bound to him by ties of discipline

and of duty. Hence come hesitation and conditions unfavorable to

daring enterprise."

On a more personal level, a New Yorker in "Battles and Leaders, vol

2, p662" wrote:

"The truth is, when bullets are whacking

against tree trunks and solid shot are cracking skulls like egg shells,

the consuming passion in the heart of the average man is to get out of

the way. Between the physical fear of going forward, and the

moral fear of turning back, there is a predicament of exceptional

awkwardness, from which a hidden hole in the ground would be a

wonderfully welcome outlet."

What could negate these natural tendencies? GFR Henderson

explains, "Mutual confidence is the force that drives a charge home;

and this quality is the fruit of discipline alone, for in almost every

campaign it is the better-disciplined troops who have displayed the

greatest vigor in assault." Henderson also cites (on p216) a

comment by Lord Wolseley, who stated that a single corps of regulars on

either the Union or Confederate side, would have won the war on account

of their superior mobility and cohesion - both traits coming from

discipline. In James I Robertson's

"Soldiers Blue and Gray", page 123, early in the war Joe Johnston is

quoted, "I would not give one company of regulars for a whole

regiment!" Relying on an army of volunteers

enlisted at the start of wars was

perhaps the country's only choice, but the quality of Civil War armies was

questionable, and this was not a new thing. In "Civil War Infantry

Tactics", Earl Hess points out

that the army of the War of 1812 did poorly with the sole exception of

Jacob Brown's army near Niagara, and in

the Mexican War, "The volunteers gained a well-deserved reputation for

lacking discipline, marauding, committing atrocities against helpless

Mexicans, and running away from battlefield dangers."

Could Civil War battles have been

decisive?

Maybe. Skirmishers weren't consistently well used. In the

French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars, skirmishers could all

but decide a battle, but we don't see that in the Civil War. The

Confederate army improved in this respect through the war, forming elite

sharpshooter battalions in each brigade, but the Union army allowed its

light infantry to decline over time. Why couldn't the Union army

have formed units similar to the Confederate brigades' sharpshooter

battalions and one-upped them by giving their skirmishers more repeating

rifles? Properly organized Union skirmishers with repeaters firing

rapidly from a prone position might have easily dominated Southern light

infantrymen - and possibly even repulse full scale attacks. Could

the cavalry have advanced with and supported infantry like in Napoleon's

time? If you accept the argument that rifled muskets were little

better than smoothbores, then maybe they could. Although admittedly

an occurrence of the smoothbore era, Jeb Stuart successfully attacked

Union infantry at 1st Manassas. Later examples were not as

successful. At Gaines Mill and at Cedar Mountain, Union cavalry

unsuccessfully attacked infantry, but these failures should come as no

surprise since these were desperate attacks by small units against

unbroken advancing infantry. British observer Arthur Fremantle in

"Three Months in the Southern States" on page 157 recounts meeting

infantry in the Western Theater,

I expressed a desire to see them form square, but it

appeared they were "not drilled to such a manoeuvre" (except square two

deep). They said the country did not admit of cavalry charges, even

if the Yankee cavalry had stomach to attempt it.

Fremantle (p 159) met a Western Theater Confederate cavalry colonel:

He explained to me the method of fighting adopted by

the Western cavalry, which he said was admirably adapted for this country;

but he denied that they could, under any circumstances, stand a fair

charge of regular cavalry in the open.

Then the colonel goes into explaining dismounted fighting and bluffing

the enemy.

Fremantle moved to the Eastern Theater and visited Stuart's

cavalry. On page 256-7 and 292:

I remarked that it would be a good thing for them on

this occasion they had cavalry to follow up the broken infantry in the

event of their succeeding in beating them. But to my surprise they

all spoke of their cavalry as not efficient for that purpose. In

fact, Stuart's men, though excellent at making raids, capturing waggons

and stores, and cutting off communications, seem to have no idea of

charging infantry under any circumstances... The infantry and

artillery of this army don't seem to respect the cavalry very much, and

often jeer at them... Staurt's cavalry can hardly be called cavalry

in the European sense of the word; but, on the other hand, the country is

not adapted for cavalry.

Perhaps fences and broken terrain with numerous woodlots made

cavalry attacks on infantry impractical. At Chancellorsville, for

example, a single Union cavalry regiment attacked down a narrow road,

unable

to change direction. Failure was the predictable result.

Lack of training and experience in the cavalry arm may also have made

it impractical. In the Confederate service, the men owned their

horses, making them less willing to risk them. Regardless of who

paid for them, horses were expensive, and it was difficult to find

forage for them in a country more sparsely populated than Europe.

European cavalry was the product of years of training, a horse alone

requiring three years to train. Further, Union cavalry were armed

with repeating rifles by late war, and in many cases served as mounted

infantry,

which meant that they largely abandoned the full potential of shock

attack, their traditional battlefield role. Late in the war, the

Union cavalry did

occasionally mount large scale shock attacks against infantry and

conducted

after-battle pursuit - at Third Winchester,

Cedar Creek, and Sailors Creek to great effect, for example. We

may never know

what could have been.

Union cavalry was handicapped from the very beginning of the war.

In no small part the problem was Winfield's Scott's attitudes

toward cavalry. Believing that

cavalry was obsolete because of advances in weapons technology, Scott

raised few cavalry regiments at the beginning of the war - a war that

would soon be over, so he thought. "Kearny's Dragoons Out West" by

Will and John Gorenfeld discusses the raising of a dragoon regiment in the

1830s. There was resistance to forming a dragoon regiment because

cavalry was perceived as expensive, European, and aristocratic -

everything that America claimed not to be. (p 23) Minimum training

time was twenty-three weeks. (p294) The Mexican War saw the

1st Dragoon Regiment broken up, never to fight as a whole regiment.

Five companies went to New Mexico, two to Taylor's army, and one company

initially assigned to Taylor going to Winfield Scott's army.

(Gorenfeld p304) Only

with the rise of McClellan were significant numbers of cavalry

regiments raised. Even then, it took time to train them, and many

were used to protect lines of supply or were dispersed throughout the

army.

It was only late in the war that the Union army had large

bodies of cavalry available. Even then, it wasn't always properly

used. Having a good body of cavalry available for the Overland

Campaign, Grant sent it on a raid to Richmond, losing not only any

usefulness on the battlefield but also its usefulness with screening

and reconnaissance. Then, facing Lee at Cold Harbor, he once again

sent his cavalry on a costly raid that was repulsed at Trevalian's

Station. The French observer DeChanal in "The American Army in the

War of Secession" was skeptical of raiding.

"After Sheridan's raid in Virginia, an

expedition which lasted more than a month, all the unserviceable horses

and broken down horses were gathered together in a park at City Point;

there were quite six thousand of them." (p29)

"The Quartermaster's Department is charged

with the duty of supplying horses for the cavalry. The number

required surpasses all belief, but it is partly explained by the

raids. These are expeditions in which the cavalry lives on the

country, traveling many miles in a few days, sometimes without finding

water or suitable forage. The greatest reason for this enormous

waste of horses, is the lack of intelligent care, natural to an

inexperienced horseman." (p 30-31)

DeChanal goes on to point out that between May and October of 1863,

the effective strength of the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac

fluctuated between 10,000 and 14,000 but the number of remounts required

was over 35,000!

"This is the equivalent to a loss of two and

one-half horses per man, or a rate of five horses per annum. And in

addition, it must be remembered that this does not include horses captured

from the enemy, which at its average, would probably amount to the entire

remount for two months." (p31)

What of the raids themselves? DeChanal cites a raid in which on

third of the horses died of thirst. In another,

"General Wilson was sent to the left of the

lines of Petersburg to cut the railroads. He succeeded in this but

was surrounded by a large force of infantry, and was able to escape with

only 3,000 cavalry, scarcely half his force, abandoning his artillery, his

prisoners, and 2,000 unfortunate negro refugees who were driven back with

strokes of sabre and lash to Richmond and sold at auction." (p 235)

Were the raids worth the cost? For a "weaker enemy", the

Confederates, for example, raids to cut communications and destroy

supplies were useful.

"But in the midst of serious operations, to

detach a considerable force to make a diversion which usually is not an

appreciable factor in the final result, is an operation of doubtful

utility. Had Sheridan's force been with Grant at Spottsylvania, a

decisive result might have resulted. Moreover, the damage resulting

from the destruction of railways is often more apparent than real.

After Wilson's disaster, the Federal forces felt consoled by the fact that

his expedition had destroyed the Danville railroad; eight days later it

was again in operation." (p 235)

Which is to say that no only was cavalry not used for combined arms

action or effectively for pursuit, its usefulness for screening and

reconnaissance was often discarded in favor of raids of questionable

value.

C-Cubed and Staffs

Earl Hess in "Civil War Infantry Tactics" points out the fact that

Civil War armies had great difficulty coordinating large attacks,

having trouble coordinating divisions and corps - much less whole

armies. In the West, the Confederate Army of Tennessee had

trouble coordinating attacks above the brigade level while its Union

counterpart, although better, nevertheless gained victory operationally

rather than tactically. In the East, the Confederate army

coordinated attacks at the brigade level at Seven Pines and Malvern

Hill and at the division level at Second Manassas and Pickett's Charge,

but in 1864 and 65, counterattacks were typically at the brigade level

- a regression rather than a progression. The Army of the

Potomac, Hess argues, was the only army of the war to regularly show

competence in coordinating attacks. At Five Forks, for example,

Gen Warren distributed copies of a map showing the plan of attack; even

still, Warren lost control of two of his three divisions and was

relieved of command by Sheridan as a result - for remaining in place so

his subordinates would be able to find him. Difficulty

coordinating - "articulation" is the word that Hess uses, made flank

attacks and the exploitation of success difficult. Frustratingly,

despite making these arguments, Hess then downplays the consequences of

the failure of Civil War armies to "regularly organize large

formations on the corps level" and makes no attempt to explain the

reasons for this failure. What were the reasons?

Issues of staff, command difficulties, military education, and

philosophy of command are key to understanding this; they were as important

as technology and tactics -

perhaps more so. A general's staff was like the nervous system of

the army; an inadequate staff made it virtually impossible to control

an army. Sharing the same background, commanders on both sides

fought using staffs that were much smaller and much less competent than

their European counterparts. For a more lengthy treatment, please

see "Staff and Headquarters in the Civil War".

Conclusion

The Civil War was not particularly advanced tactically, but it was not

fought using the tactics of Napoleon I either. Regardless of the

reasons - technology, tactics, terrain, command and control problems -

or more likely a mixture of all these things - circumstances tended

toward making Civil War combat less decisive than Napoleonic

combat. Whether Napoleonic combined arms cooperation was still

possible on a large scale during the Civil War is debatable. But

the advent of rifled muskets doesn't explain this failure.

Advances in artillery technology had more effect, but even these

changes don't offer a complete explanation. Command, control, and

communications problems, along with difficult terrain, made decisive

battle more difficult to achieve. When victory was achieved, pursuit

was often half-hearted and limited to the speed of infantry since cavalry

was scarce. Numerous are the examples of

Civil War battles on the verge of decisiveness - but without that final

step that would have annihilated the enemy - Shiloh, Second Manassas,

Antietam, Gettysburg, Chickamauga. Perhaps this failure to

achieve decisive results encouraged the late-war custom of entrenching,

although there are other explanations. The Prussian observer

Justus Scheibert argued that breastworks were "safeguards against

panic". (Scheibert 50) Earl Hess argues that

troops entrenched as a reaction to the shock of battle. The

effectiveness of artillery perhaps contributed to the practice.

Others

point out that entrenching freed up troops to turn or flank the enemy -

so entrenching was essentially a method to facilitate maneuver - one

which had the opposite effect. GFR Henderson saw a relationship

between entrenching and enemy discipline. He wrote,

"Very early in the War of Succession, the

Federal commanders, recognizing their enemy's disposition to bring

matters to a speedy issue, made use of earthworks and entrenchments;

the Confederates, at a later period, when the desperate assaults on the

Fredericksburg heights taught them that the Northern battalions had at

length learnt to follow their officers to certain death, gave up their

trust in broken ground and sheltering coverts, and adopted the same

means of stiffening the defence. In 1863, the third year of the

war, both armies became equally formidable on the defensive, ... (and)

the confusion of the earlier fields of battle was no longer seen."

Only one side had to entrench in order to force their opponent to do

so. To do otherwise was just too risky, and there was no turning

back. All of these explanations above have validity. The 1864

campaigns little resemble those of 1862 or 1863. Battle lines

were stretched thinner, putting commanders even more out of touch with

the situation, and making armies even more difficult to control than

before. At any rate, battle tactics had failed. Perhaps the

use of entrenchments was inevitable, with a bloody attritional struggle

like the Overland and Petersburg Campaigns being the predictable

result. Eventual Union victory was the result of

operational successes like Vicksburg and Appomattox - and not from

the destruction of enemy armies on the battlefield.

Sources and Suggested Reading:

Michael A. Bonura, Under the Shadow of Napoleon

Bowden and Ward, Last Chance For Victory

David Chandler, Art of Warfare in the Age of Marlborough, The Campaigns

of Napoleon

Phillip Cole, Civil War Artillery at Gettysburg, Command and

Communications Frictions in the Gettysburg Campaign

Jean Colin, Transformations of Warfare

DeChanal, The American Army in the War of Secession

Christopher Duffy, Instrument of War: The Austrian Army in the

Seven Years War

Robert P Epstein, Napoleon's Last Victory and the Emergence of Modern

War

Lee W. Eysturlid, The Formative Influences, Theories, and Campaigns of

the Archduke Carl of Austria

Steven Fratt, The Guns of Gettysburg - North & South August 2004

Arthur Fremantle, Three Months in the Southern States

Gates, David, The British Light Infantry Arm, c. 1790-1815

Gorenfeld, Will and John, Kearny's Dragoons Out West

Paddy Griffith Battle Tactics of the Civil War, Forward Into

Battle, Battle

Edward Hagerman, The Civil War and the Origin of Modern Warfare

William Hazen, A Narrative of Military Service

GFR Henderson, The Science of War

Earl Hess, Field Armies and Fortifications in the Civil War

Earl Hess, Civil War nfantry Tactics

Ian Hope, A Scientific Way of War

Wayne Hsieh, West Pointers and the Civil War

BP Hughes, Firepower

Robert K Krick, Stonewall Jackson at Cedar Mountain

Brent Nosworthy Anatomy of Victory, With Cannon Musket and Sword, The

Bloody Crucible of Courage

Peter Paret, The Cognitive Challenge of War: Prussia 1806

Christopher Perello, The Quest for Annihilation

Robert Quimby, Background of Napoleonic Warfare

Fred Ray, Shock Troops of the Confederacy

Carol Reardon, With a Sword in One Hand and Jomini in the Other

Justus Scheibert, A Prussian Observes the American Civil War

Moxley Sorrel, Recollections of a Confederate Staff Officer

Arthur Wagner, Organisation and Tactics

Geoffrey Wawro, The Austro-Prussian War, The Franco-Prussian War

Copyright 2008-24, John Hamill

Back

to Civil War Virtual Battlefield Tours