Cowpens

January 17, 1781

New research has drastically revised

the traditional story of the Battle

of Cowpens. The book

"A

Devil of a Whipping: The Battle of Cowpens"

by Dr. Lawrence

Babits, using Dr. Bobby Moss's studies of pension statements and other

new sources, reflects these changes,and the virtual tour below is

intended to reflect this new

version and incorporates some suggestions from John Robertson,

who works at the site.

The South

was spared the ravages of war for much of the

Revolution. A Tory rising was quashed at Moore's Creek, and

the British

attempt to capture Charleston in 1776 also failed.

The British captured Savannah

in 1778, and in 1779 a combined American and French force failed to

retake

the city by storm. Charleston was taken in 1780

and most of the Virginia Continental Line was captured there.

Gen. Gates was sent South but was soundly defeated at Camden

in August. Only the mountain men's destruction of Ferguson's

column at King's Mountain

in October prevented Cornwallis from invading North Carolina in late

1780. Stanley Carpenter, in "Southern Gambit" argues that the

British "clear and hold" strategy was built on faulty

assumptions of Loyalist support, that Loyalists

would occupy that territory cleared of the enemy by

regulars. Nevertheless, the strategy had a chance to succeed

with patient, conservative leadership. Cornwallis,

however, was impetuous by nature, and supply difficulties made it

difficult to keep an army in one location. British policy was

based on the successful suppression of Jacobite rebellions, but in the

American South this failed to attract Loyalists because they perceived

it as too lenient while it pushed paroled patriots back into the war

because they perceived it as too harsh. Eventually it also

alienated neutrals. Seeing that patriot irregulars were

supported by the colonies further north, Cornwallis was eager to

advance into North Carolina and Virginia before South Carolina was

fully secure.

Gen. Nathaniel Greene was

appointed by George Washington to command the Southern Army.

Greene joined his army in Charlotte on December 2,

1780. Greene had only about 2,400 men to face Cornwallis'

4,000

men. Stopping Cornwallis with conventional methods would be

impossible, and feeding the entire army at one location was

impractical,

so Greene adopted a hybrid conventional/irregular strategy that would

exploit Cornwallis's personality. Greene detached Gen. Morgan

with 600 men into the direction of Ninety-Six

while Greene himself moved to Cheraw with 1,100 men. Lt. Col.

Henry

Lee was sent to assist Francis Marion in raiding British lines of

communication

in eastern South Carolina. Although Greene had divided his

already

weak force, it was positioned so that Cornwallis could not advance into

North

Carolina without exposing his flanks and rear, and it allowed Morgan to

rally militia in the backcountry.

In

response Cornwallis detached

Lt.Col. Banastre Tarleton with 1,100 men

to deal with Morgan. Tarleton's force, a light strike force,

included his Legion with

250

cavalry and no more than 271 infantry, about 50 men of the 17th Lt.

Dragoons,

263 men of the 71st Regiment, 177 men of the 7th Regiment, several

companies

of Light Infantry amounting to no more than 160 men, and two 3

pounders.

Morgan withdrew in the face of Tarleton's advance and

stripped

the

country of forage. On January 16th, Morgan stopped five miles

short

of the Broad River to make a stand. He had 300

Continentals

and

other reliable troops. Under William Washington, a cousin of

George,

were 82 Continental cavalrymen, no more than 45 state cavalrymen, and

additional

militia for a total of no more than 150 men. Militia units

had

been

arriving, and it is now thought that Morgan's force totaled around

2,000 men, which is roughly the number that Tarleton thought that he

had faced.

The night before the battle, Morgan

went to the soldiers'

camps and told his men about the battle plan, and he reminded them of

Tarleton's massacres and that if they ran, they would be

trapped at

the Broad River. On the morning of January 17, 1781, Morgan's

men had

a hearty breakfast and awaited the enemy. Tarleton feared

that Morgan

would slip away, so he awakened his men at two o'clock in the morning

to

begin the four mile march to Cowpens. At 6:45, Tarleton's

cavalry

screen reached the clearing at Cowpens.

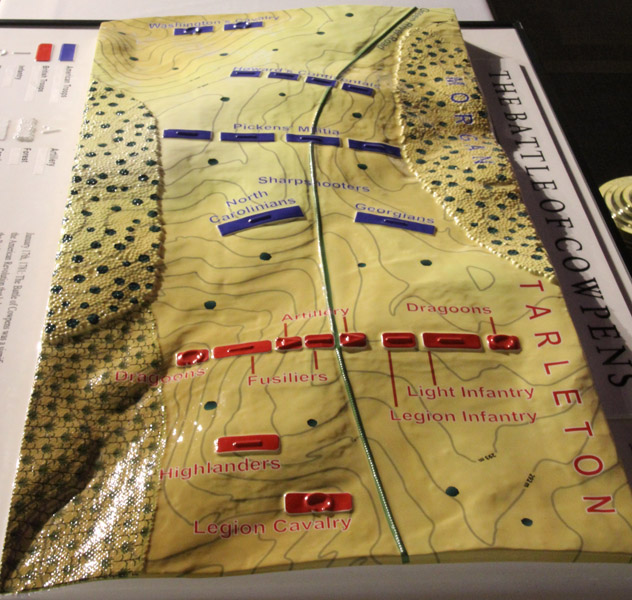

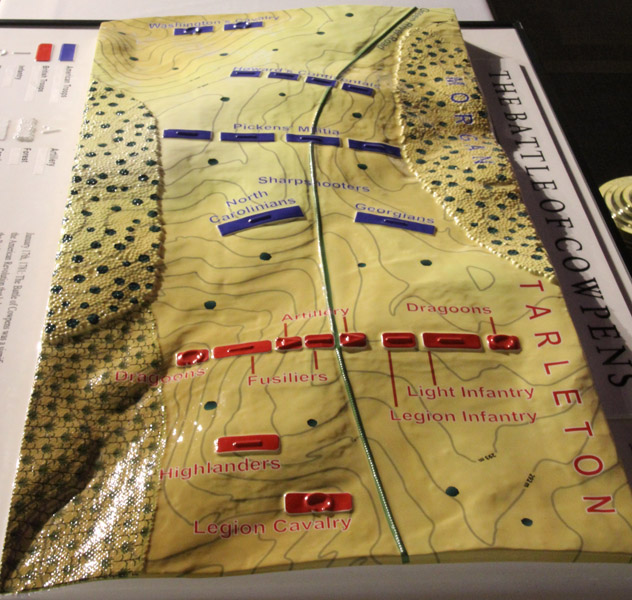

Books on the battle often include

schematic maps that do not accurately represent the terrain.

The NPS visitors center includes this great relief map.

The round green dots represent woods that protected both

American flanks. The other green symbols are canebreaks, a

native form of bamboo.

British Deploy and

Attack

| Tarleton and his men reached this

clearing and saw an

American force deployed in front of them. This is a view from

the

(British) left

side of the clearing called Hannah's Cowpens. In the flat

land in

the foreground there was low swampy ground known as 'the

rivulet',

an area which is now more firm. American

riflemen from Georgia and the Carolinas served as a skirmish

line

behind

it further uphill, but also extended toward the woods on their right.

These are the faint gray woods in the background.

Further

back, behind the small hill on the left of the

picture stood the South Carolina militiamen under Gen. Pickens.

In

the woods on the far left of the picture, the flank was protected by a

ravine with a stream and canebreaks. On the other

flank near

the woods, and protecting that flank,

were two heads of a stream also with canebreaks. The militia

line

was

anchored on each of these obstacles, and was positioned behind the hill

because

troops firing downhill tend to fire over the enemy's heads.

Behind the militiamen, not visible

to the British, but

on or beyond a slightly higher extension of the ridge near were it

moves back, were the Continentals and Virginia militia under Lt. Col.

John

Howard. At the far end of the clearing, and hidden the

hill was the cavalry under William Washington.

Tarleton deployed to attack with each

flank protected by 50 cavalrymen. The infantry from

right to left were the Lt. Infantry, the Legion Infantry, and the 7th

Regiment.

Two 3 pounders were deployed on either side of the 7th.

Further

to the left, and somewhat behind, was the 71st Regiment. In

reserve

were the 200 men of the Legion cavalry.

|

Canebreak

|

View From Skirmish Line

The British advanced toward the

American skirmishers,

who after firing a few shots withdrew. They would join the

militia line.

Militia Line

Canebrakes protected both flanks of the

American

militia line. Hayes' Bn., one of the four

units of Pickens command, had advanced ahead of the militia

line on the left side of the road. The

skirmishers

withdrew around this

unit and to the flanks of Pickens' line, and Hayes fell back

into

line.

The

British infantry continued the advance and were met

with a volley at under 100 yards. Despite their high losses,

the British

kept coming, and the militiamen fell back in confusion behind the

Continentals.

The Virginia militia units flanking the Continentals had

temporarily

withdrawn en echelon to allow the passage of the first line militiamen.

View from Continental Line

of John Eager Howard

Morgan moved to rally Pickens' men.

Skirmishers

from the front line had withdrawn to Howard's left flank.

These men

did not have bayonets, and as the British continued to advance, their

cavalry rode over the skirmishers and into Pickens'

militia. They came under

fire from the Continental line. William Washington's

cavalry had been stationed in a low area, probably in the area west of

the trail from the visitors center. Their position had

been concealed from the British, but cannonballs

rolled into

their position. Washington came out from hiding with

half of his cavalry, smashed into Ogilvie's British cavalrymen, and

forced them from

the field.

Despite having his flanking cavalry

routed, Tarleton continued the advance on the Continental line,

possibly not seeing most or all the line and simply pursuing the

militiamen. The British advanced and exchanged several

volleys

with the Continentals. On the British left, the 71st Regiment

was brought

up to flank the American right.

When the

71st Regiment moved against the American right, Howard ordered

the flank refused. This created confusion, and the whole line

began

to retreat. Seeing this, Morgan selected a new line and had

his troops

face about and fire. Near the Washington Lt Infantry Monument

is where the Continentals

were positioned, possibly lying on the ground. As the British

rushed toward them, the Continentals leveled a devastated fire on the

disorganized British. Washington's cavalry had moved to the

American

right to protect the flank and rear of the militia from

the 71st

Regiment and now moved around the American right to attack the

rear of the British line. While

Washington smashed into the flanking British cavalry and moved

into the British rear, Howard's line charged.

Hundreds of

British troops were encircled, and they threw down their weapons to

surrender.

Tarleton rushed to his Legion cavalry

and ordered them

to attack and save the day, but they fled the field. Tarleton

instead

counterattacked with 54 officers and men, but after some success, he

was repulsed.

The Continentals continued the pursuit and captured the two 3

pounders,

their crews fighting to the death.

The battle

is a tactical

masterpiece admired to this

day. The American regulars suffered only 12 killed and 60

wounded,

but also counting the militia would probably double the

figure.

The

British suffered 100 killed, 229 wounded, and 600 captured.

Only

the

200 Legion cavalrymen escaped. Strategically, the British

were

significantly knocked down to size, making the conquest of the South

much more difficult. Compounding the loss in numbers, those

lost had been from the British light strike force, also used

for reconnaisance. Cornwallis pursued Morgan but failed to

cut

off his

retreat. He believed that if he didn't advance into North

Carolina and Virginia, he couldn't hold South Carolina and Georgia.

The British pursuit had been slow, covering only 22 miles in

seven days compared to the patriots marching 100 miles in five days.

Cornwallis decided that now was the time for drastic action,

so he burned his baggage, resulting in 250

desertions, and recklessly pursued Morgan and Greene

to the Dan River in Virginia. Hearing that Cornwallis had

burned his baggage, Greene decalred, "He is ours!" As

Cornwallis weakened, Greene got

stronger.

Down from 4,000 men to less than 2,000, Cornwallis

fought at Guilford

Courthouse, and after the battle Cornwallis was

so weak he had no hope of holding on

to North Carolina. Instead, he fell back to

Wilmington, then advanced

into Virginia. There, in October, he was forced to surrender

at

Yorktown.

Back

to Revolutionary War Virtual

Battlefield Tours